A city in China’s Xinjiang province has temporarily banned people with veils, head scarves and long beards from boarding buses. Experts say attempts at repressing their culture are fueling violence and extremism.

On August 4, in the northwestern Xinjiang city of Karamay, authorities announced a ban on people with head coverings including hijabs, niqabs and burkas, or beards, from taking local buses. The ban would apply for the duration of a sports competition ending on August 20, state media reported.

For Uighurs, a Turkic-speaking Muslim minority, these restrictions are just the latest in years of oppression by the Chinese government, say analysts. Uighurs’ rights, culture and language have suffered for years under repressive policies from Beijing, religion has remained a lifeline, said Ümit Hamit, vice president of the World Uighur Congress (WUC). “Now the Chinese government wants to destroy the only relief the Uighurs have left.”

For Uighurs, a Turkic-speaking Muslim minority, these restrictions are just the latest in years of oppression by the Chinese government, say analysts. Uighurs’ rights, culture and language have suffered for years under repressive policies from Beijing, religion has remained a lifeline, said Ümit Hamit, vice president of the World Uighur Congress (WUC). “Now the Chinese government wants to destroy the only relief the Uighurs have left.”

The new rules, which also forbid anyone wearing clothing with the Islamic star and crescent symbol from boarding buses in the area for the specified duration, follow a ban last month by some schools and government offices in the region on students and staff fasting during the month of Ramadan. This was enforced as a measure to prevent the promotion of religion in schools and public offices.

With an Uighur population of around 45 percent, Xinjiang is a majority Muslim region. Although China’s constitution states that citizen’s “enjoy freedom of religious belief” and condemns discrimination (article 36), the atheist, Communist-run government pursues secular policies.

Uighurs make up 45 percent of the population in Xinjiang

Uighurs make up 45 percent of the population in Xinjiang

Lack of ethnic integration?

Elsewhere in China, Muslim minorities continue to practice their religion without the new restrictions. For instance, the Hui people, a predominantly Muslim ethnic group, speak Chinese as their mother tongue and practice a different form of Islam, strongly influenced by Chinese traditions.

For this reason, restrictions in the country’s northwest on expressions of Islam such as headscarves have been interpreted by experts and rights groups as yet another attack on Uighur culture. “This ban is not against Islam per se but specifically targeting the Uighurs,” says Enze Han, a specialist on ethnic politics in China at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London.

It follows growing violence in the region, including clashes which killed dozens last month, an incident Beijing condemned as a terrorist attack by Islamist and separatist groups, fueled by a lack of ethnic integration.

“Recent policies are seen as a way of breaking down cultural barriers between Uighur and other Chinese communities,” said Edward Schwarck, an Asia expert at the UK-based Royal United Services Institute for Defense and Security Studies. “Yet there is a clear failure by Beijing to see that, ultimately, integration cannot be brought about through coercion and violence,” he added.

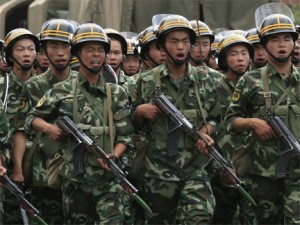

The Chinese government announced a one year crackdown on violence in Xinjiang after a bomb attack in May

The Chinese government announced a one year crackdown on violence in Xinjiang after a bomb attack in May

Vicious circle

“There is clearly a causal link between hard-line law enforcement and Uighur violence,” says Schwarck, explaining that bans on everyday expressions of Uighur culture are “deeply provocative and frequently spark violent reactions.” Now there are fears that the increasing repression of their culture is leading to radicalization among the Uighurs, WUC vice president Hamit told DW. The government then accuses them of terrorism, leading to a vicious circle of violence.

Accusations are flying from both sides – while Beijing blames recent attacks and violence on Uighur “terrorists,” the Uighurs deny these claims.

“At the moment there is no official radicalized or Islamist group who want to support the Uighurs,” said Hamit, alleging that the government is even propagating this idea by setting up fake websites for terrorist organizations purporting to be Uighur-run groups.

China has increased security in many parts of the restive Xinjiang province following some May’s attack.

Radicalization

The murder of a leading Imam in Xinjiang’s city of Kashgar, at the end of July, has also contributed to concerns over religious extremism. Some Uighurs have travelled to countries in the Middle East, where religious extremism is widespread, in order to be trained to act against the Chinese government, Hamit said, suggesting that this could have disastrous consequences.

According to Asia expert Schwarck, the real danger remains to be seen. “It is not yet clear to what extent Uighurs in Xinjiang are being exposed to Jihadi thinking from outside China.”

Leave a Reply