The psychology behind global support for China’s South China Sea position: a desire to avoid war.

The South China Sea arbitration case has elicited almost unanimous public opposition in China. Besides this, it has been reported that 66 countries worldwide have endorsed China’s position on the South China Sea. Yet that figure also caused controversy, especially in the United States.

According to our team’s research, we have found at least 70 countries supporting China’s position on various occasions. We find that the reason for the controversy over the figure comes down to different definitions on “China’s position.” But no matter how it is defined, the psychology behind these statements is a desire to avoid taking sides between China and the United States, showing the reality of a fundamental global consensus on peace and wide-spread anxiety toward the potential for conflict in the South China Sea. Thus, we should take every opportunity to go beyond the “zero-sum game” in order to maintain peace in the South China Sea, to seek Asia-Pacific economic cooperation, and to make the “cake” bigger using economic and financial means.

How many countries support China’s South China Sea position?

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

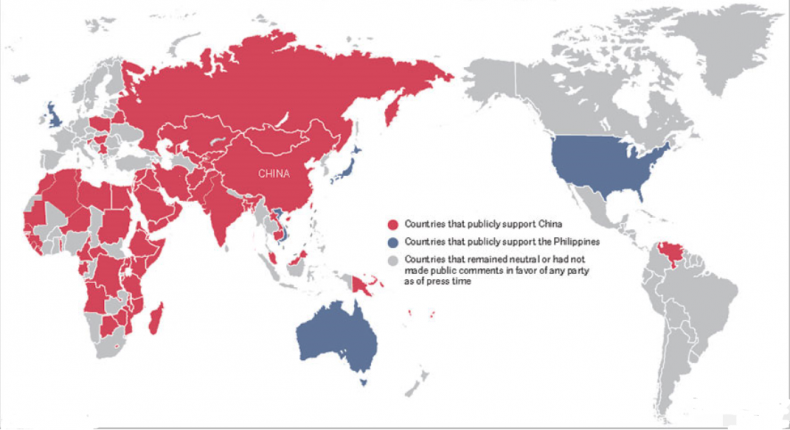

There is no doubt that Chinese almost unanimously support their government’s official position on the South China Sea, shown by the firestorm of social media comments soon after the award. Moreover, China’s position is also welcomed and understood by other countries. According to the Chinese government and media, nearly 100 parties from more than 60 countries declared their support for China’s position on the South China Sea issue. China Daily counted 66 countries, as shown in the map below.

The figure, however, encountered doubts from American media and think tanks. The Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative argued that the real number was only ten. We personally also received emails expressing similar doubts.

Considering such a huge gap in the count, our research team at the international studies department of Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China (RDCY), sought to verify on our own by conducting an independent count. We explored the issue by extensively searching the internet, and then looked for original sources including media reports, official statements, diplomatic documents, and talking points. We also searched the Chinese foreign affairs database, Xinhua‘s news and multimedia database, and our news citation system with data from various sources such as Bloomberg and Reuters to verify.

Strikingly, we identified 71 countries that have expressed their support for China’s position, even more than reported by Chinese media. In addition, the League of Arab States and Shanghai Cooperation Organization are also in line with China. (We have listed the countries and sourced all of the statements, with the date of issue, in the appendix below). It is said some others privately expressed support to China according to our global network, but we only counted the countries that went on record. It is also possible that our team may have miss some countries that are supporting China.

Why is there such a big gap in the number?

One reason is quite obvious: some of these statements of support are not available in English. They are expressed and available in Chinese, French, Spanish, Arabic, Swahili, Khmer, or other languages. Therefore, some analysts in the English-speaking world may have merely failed to find them.

More importantly, though, the discrepancy has something to do with the essence of “China’s position.” Simply put, we suppose most American media and think tanks have not yet understood what “China’s position” means. In our view, China’s position on the South China Sea issue can be interpreted as below:

- China does not participate in the arbitration, nor accept, recognize, or implement the award.

- China will adhere to peaceful negotiations and settlements of the South China Sea dispute.

- While disputes should be settled by the parties directly concerned in accordance with the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC), China will work with ASEAN countries to maintain peace and stability in this region.

- The temporally-established (ad hoc) arbitral tribunal is neither a part of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) nor the International Court of Justice (ICJ). It does not have jurisdiction over the territorial disputes, which is the core of the arbitration. The arbitration itself is flawed in procedure. Thus, the award is not legally-binding, nor representing international law.

To directly support any of those components is to support China’s position. On the contrary, those countries that openly endorse the arbitral tribunal as affiliated to PCA and assert China should recognize and implement the award oppose China’s position.

In this regard, at least 70 countries, based on our research, endorse China’s position in various angles of the four components above, and they did so in various ways: unilaterally, bilaterally, or multilaterally. All of them welcome peaceful negotiations to settle the disputes. In addition, we should bear in mind that Philippines’ ex-parte arbitration violates its own commitment to peaceful dialogue and negotiation. Among these countries, some expressed their public and firm support for China’s stance of non-acceptance of the arbitration. Nonetheless, “non-acceptance” is only part of China’s position. American media and think tanks who use this alone for their counts misinterpreted the implication of China’s position.

Generally speaking, most countries’ attitudes toward the South China Sea issue can fall into three categories.

Counties in the first category, represented by Japan, oppose China’s position by supporting the Philippines’ stance while insisting China should recognize and implement the result of the arbitration, which is claimed to officially represent the PCA. This opinion is rare. China Daily mapped five in its report, but our team can only identify three: Japan, Australia, and the United States. Vietnam and the United Kingdom, though represented on the map, do not meet the definition of opposing China directly. In this circumstance, although Japan indeed raised the issue at the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) in Ulaanbaatar, it was echoed by no country except the Philippines itself, according to Japanese media such as Japan Today, The Japan Times, and The Japan News.

The second group includes countries that explicitly expressed their firm support to China on the arbitration, such as Pakistan, Cambodia, and some African countries. This group is bigger than the first one, but still limited. For example, in a public speech broadcast on TVK, Cambodia’s state-owned television network, on June 20, Prime Minister Hun Sen revealed diplomatic pressure over the South China Sea from “certain country outside the region” — widely believed to refer to Japan — and expressed his objection to the arbitration. In a press release found on the official website of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Pakistan on July 12, the Chinese neighbor reiterated its support for China on its statement of optional exception in light of Article 298 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Among African countries, Kenya issued a statement on June 15, also on its MFA website, declaring its respect for China’s right of optional exception under UNCLOS Article 298. Gambia, another coastal country in West Africa, has stated its support of China’s position on the arbitration by clearly saying the arbitral tribunal has no jurisdiction over delimitation in the South China Sea through the Gambia Radio and Television Service (GRTS).

Last, many countries, categorized as the third group, support China’s position in terms of resolving the disputes through consultations and negotiations while following the Declarations on the Conduct of Parties in South China Sea (DOC). Combining the second and the third groups, we have found 71 countries, with probably some still missing. Our global think tank network and foreign embassies in Beijing told us some other countries also hold similar attitudes, but have not openly expressed their position due to some “pressure.” We did not include them in our count.

Therefore, our key finding is that the claim by Chinese officials that at least 66 countries support China’s position is verified and solid; in fact, we found five more countries. Although the second and third groups as outlined above may have different stresses on China’s position, they all welcome at least one of the four components. Considering China’s official position on the peace negotiations, these two types of opinions acknowledge the path of peace talks.

Further, the fact that most countries do not show a hardline stance toward either China or the United States illustrates their anxiety about conflicts. This psychological factor is the fundamental issue behind the rally of support.

The Root Cause: Anxiety Over Conflict

In our opinion, the moderated stances of most countries can be explained by the global fundamental consensus over the South China Sea issue — a desire for peace. However, some people are worried about the possibility of an armed clash in the South China Sea and even the start of a “new Cold War” which may force countries to take sides between the United States and China. From this point of view, those who assert that only 10 countries support China not only too narrowly define “China’s position,” but also fail to fully recognize the nuance of other countries’ positions. Moreover, whether the count is 10 or 70, the real issues behind these statements are the global consensus on peace and worldwide anxieties or even fears of conflict — or worse, war.

In recent years, conflicts and turbulence have risen across the world. Thus, there are great anxieties about social unrest and mass violence; there are also anxieties about the distrust between major powers, which may very likely result in a new Cold War or even hot wars if badly managed.

East Asia has long been called “The Museum of Cold War,” where long-standing geopolitical and traditional security issues have not yet been settled and even have been heating up in recent years, especially after the “pivot to Asia” was introduced.

Recently, the South China Sea has been the focal point of Sino-U.S. relations. However, when it comes to the South China Sea issue, some countries find themselves trapped into a dilemma: not only do they worry about the loss of economic support from China, but also they are worried about the loss of security support from the United States. Moreover, some may worry that the regional organization they belong to will be split by the South China Sea issue.

Besides Cambodia mentioned above, Singapore and Thailand have also stated that they will not be involved in the disputes and called for peace. Further, ASEAN as a whole did not form a unanimous view after the arbitration, which shows even ASEAN countries try to avoid taking sides between the two giants.

A great portion of China’s support comes from African and Middle Eastern states that call for diplomatic negotiations rather than unilateral actions. This is not surprising given their collective history as colonies and the deteriorating security environment in these regions.

Extremism is on the rise while the South China Sea heats up. In one of our seminars in Washington D.C. recently, Professor Amitai Etzioni of George Washington University reminded us that the United States’ active response to terrorism and extremism in the Middle East and Africa will also guarantee its credibility among allies without taking on the risk of conflict with China; meanwhile, China has many common interests with the United States on anti-terrorism issues.

Take a look at the tragedy in Nice, think about the death toll in Kabul, let alone the long-lasting bloody turbulence in the Middle East, then you will probably agree with our conclusion: it is time for China and the United States to work together to address our common threats — terrorism and extremism — instead of focusing on the current zero-sum game in the South China Sea.

Beyond the Zero-Sum Game: Seek Asia-Pacific Cooperation

When former Chinese State Councilor Dai Bingguo famously said the arbitral award is nothing but “a piece of waste paper” in the U.S.-China Dialogue on the South China Sea held by our institute (RDCY) and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, we have almost forgotten his key point is that we need a cooling down. Indeed, no matter how the public reacts to the arbitration, the “fusing point” — July 12 – has already passed; all parties are evaluating the next step in the game and restarting the long-term setup for the region. As we mentioned above, peace, the real and fundamental global consensus, remains there. Whether parties want it or not, the disputes will be settled in peace while regional cooperation will continue.

In fact, even in the Philippines there is an effort toward peace. Rodrigo Duterte, the new president, has shown a low-key, restrained, and cooperative attitude after the arbitration. It is reported that Fidel Ramos, a former Philippine president (and also the authors’ friend), will visit China as an envoy. All these efforts show that peace and stability remain the common interests of all parties of the South China Sea in the “post-arbitration” era.

This also goes for the United States. As Jeffery Bader of the Brookings Institution wrote in his recent “framework for U.S. policy toward China,” despite the disputes over the South China Sea issue, China is still a vital stakeholder in global governance and shares a lot of common interests with the United States. In particular, China is going to hold the G20 summit in Hangzhou — a chance for China to lead the global economy recovery cooperatively with other G20 members, including the United States. So why can’t the two cooperate on the South China Sea?

There have been good signs, in fact. Admiral John Richardson, the U.S. chief of naval operations (CNO) paid a successful visit to China on July 17-20, having a fruitful talk with his counterpart Adm. Wu Shengli. We hope this visit will serve as a new starting point for Sino-U.S. military exchanges after the arbitration.

Furthermore, cooperative governance is plausible in the South China Sea. As the authors said at the U.S.-China Dialogue, the most devastating threat to the fishermen in and around the South China Sea is not from China, nor from the United States, but from typhoons. In this regard, all parties, including China and the United States, can cooperate on issues such as meteorological stations, data sharing, typhoon early warning systems, and joint research on climate change. When it comes to hard military issues, the mechanism for Sino-U.S. cooperation already exists. China has taken part in the RIMPAC exercises twice now; in fact, as we wrote this piece, one Chinese fleet was exercising together with U.S. Navy around Hawaii. It is time to freeze tensions as well as activating the existing military exchanges.

We should also bring joint development and broader economic cooperation back to table. Recently, the Duterte government has expressed its will to cooperate with China in exploiting the resources of the South China Sea. The Philippines have some maritime area in the South China Sea that are not subject to sovereignty disputes, but does not have the technology and investment to benefit from them. Here China can do something for the Philippines. This prospect recalls the suggestion to shelve differences and seek joint development put forward by former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping when meeting with a former Philippine leader.

Finally, as we wrote in our previous article, the South China Sea issue will not stop China-ASEAN economic and financial cooperation. The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road initiative and Mekong-Lancang Mechanism initiated by China are shaping more diversified development projects, and a more flexible and open win-win situation where all ASEAN countries can obtain the investments that they urgently need, including in the sectors of manufacturing, infrastructure, and what we call the “financial infrastructure.” Moreover, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) is a financial institution with strong compatibility and feasibility. The Philippines joined the institution as a founding member; of course, Japan and the United States are welcome to join and benefit from AIIB as well.

To conclude, to avoid a war and to maintain peace in the South China Sea and the Asia-Pacific is the real and fundamental global consensus behind the divergent views on “China’s position.” To make a difference, China, the United States, and other countries should bring joint development back and focus more on possible cooperation areas from anti-terrorism to economic and financial ties, eventually leading the global economy out of its sluggish and uneven recovery.

Wang Wen is the Executive Dean of Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China (RDCY); Chen Xiaochen is a researcher of RDCY; Chang Yudi, an intern researcher of RDCY, contributed the piece. Our research team also includes Cheng Yang and Zhou Ximeng, RDCY research assistants, Su Yue and Dong Yi, RDCY interns.

Appendix

The 71 countries that publicly support China’s position over the South China Sea dispute, with the dates of when that support was declared, stated, published, or released by diplomatic documents, talking points, or the media. Note that some countries made many statements; we have selected only one per country.

Africa (39):

- The Republic of Kenya 06/15/2016

- The United Republic of Tanzania 05/31/2016

- The Republic of Zambia 06/13/2016

- Republic of Cameroon 06/15/2016

- The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia 06/15/2016

- Kingdom of Lesotho 05/27/2016

- Republic of Malawi 06/22/2016

- The Republic of Mali 07/06/2016

- The Republic of Niger 05/19/2016

- The Republic of Uganda 05/30/2016

- The Commonwealth of Eritrea 05/30/2016

- The Republic of Sierra Leone 06/09/2016

- The Gabonese Republic 05/12/2016

- The Central African Republic 06/28/2016

- Madagascar 07/08/2016

- The Republic of Guinea-Bissau 06/24/2016

- The Republic of Guinea 07/19/2016

- The Republic of Benin 07/11/2016

- Democratic Republic of the Congo 06/28/2016

- Republic of Zimbabwe 06/30/2016

- The Republic of Angola 07/01/2016

- The Republic of Liberia 07/05/2016

- The Republic of Senegal 07/08/2016

- The Republic of Tunisia Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- The Kingdom of Morocco Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- The Republic of Mozambique 05/18/2016

- The Republic of Congo 06/20/2016

- The Republic of Burundi 05/18/2016

- The Republic of Togo 05/17/2016

- People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- The Republic of Sudan 04/28/2016

- The Republic of Djibouti Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- State of Libya Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- The Islamic Republic of Mauritania Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- The Somalia Democratic Republic Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- Union of Comoros Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- Islamic Republic of Gambia 04/21/2016 Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- The Republic of South Africa 06/22/2016

- The Arab Republic of Egypt Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

Asia (23):

- Yemen Republic Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- Sultanate of Oman Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- Nation of Brunei 04/23/2016

- Republic of Lebanon Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- The Syrian Arab Republic Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- Republic of Iraq Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka 04/09/2016

- Islamic Republic of Afghanistan 05/18/2016

- People’s Republic of Bangladesh 04/27/2016

- Lao People’s Democratic Republic 04/23/2016

- Kingdom of Cambodia 04/23/2016

- The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- Kingdom of Bahrain Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- Republic of Uzbekistan 06/24/2016

- The State of Palestine Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- Kyrgyz Republic 04/27/2016

- Republic of Tajikistan 06/24/2016

- State of Kuwait Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- State of Qatar Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- Islamic Republic of Pakistan 04/28/2016

- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- United Arab Emirates (UAE) Doha Declaration 05/12/2016*

- Republic of Kazakhstan 04/28/2016

Europe (4):

- The Russian Federation 04/29/2016

- Republic of Serbia 06/19/2016

- Montenegro 07/12/2016

- The Republic of Belarus 04/27/2016

South America/Caribbean (3):

- Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela 05/10/2016

- Grenada 06/24/2016

- The Commonwealth of Dominica 06/24/2016

Oceania (2):

- The Independent State of Papua New Guinea 07/08/2016

- The Republic of Vanuatu 05/25/2016

International Organizations (2):

- League of Arab States 05/12/2016

- Shanghai Cooperation Organization 06/24/2016

* These countries expressed supporting to China’s position on the South China Sea issue in the Doha Declaration jointly adopted at the 7th Ministerial Meeting of the China-Arab States Cooperation Forum on May 12th, 2016.

Source: thediplomat.com

Leave a Reply