The Chinese government has imposed another in a long list of absurd restrictions in the northwest province of Xinjiang, banning the use of certain Muslim names in a supposed effort to “fight terrorism”, and giving news outlets an opportunity to run with eye-popping and sensationalist headlines.

“China Bans ‘Muhammad’ and ‘Jihad’ as Baby Names in Heavily Muslim Region” read a headline in The New York Times on 25 April.The Daily Mail went one better running with “No Jihad, Imam or Saddam: China ‘bans extreme Islamic baby names’ among its Muslim population”.

It cannot be stressed enough that the China’s severe religious restrictions such as the Ramadan ban, and now prohibition of certain Muslim names, is a manifestation some of the most extreme Islamophobic policies in the world. Amnesty International’s annual 2016-2017 report claims that in Xinjiang “The government continued to violate the right to freedom of religion, and crack down on all unauthorized religious gatherings” despite the government’s claims of progress on maintaining “social stability”.

Yet the obsessive media focus on Muslim identities of the Uighurs obscures the ethnic roots of the conflict, and China’s complex relationship with its various Muslim communities; only helping the Chinese government’s public relation efforts to falsely tie the unrest in Xinjiang to the nonsensical and western-led “War on Terror” while attempting to relieve it from scrutiny.

The Uighurs: A group vying for autonomy

Xinjiang’s history of struggle for independent dates back to the 18th century when the Qing dynasty annexed the Uighur majority region. The area was briefly declared independent in 1949 and called East Turkestan, before the Communist Chinese government under Mao wrestled control of the province. Hostilities have since been ongoing, escalating from time to time forcing the Beijing power centre to clampdown in the northwestern province.

Notably, tensions in the province escalated in the 90s as Soviet Republics such as Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan gained independence, sparking a drive for self-determination in the province, and subsequent fighting between the state and separatist forces.

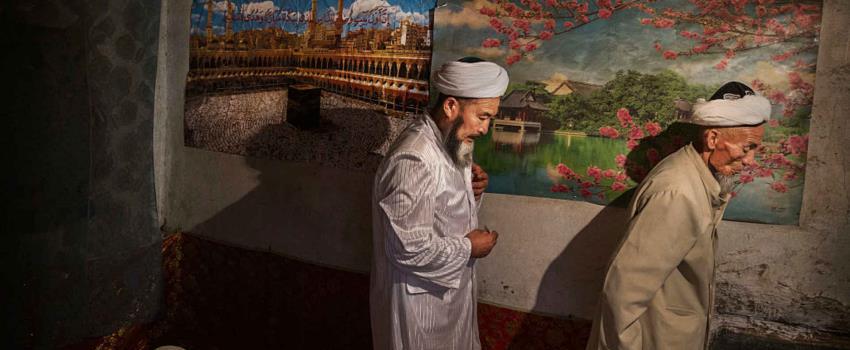

| Xinjiang province is home to some 10 million of China’s Muslim Uighur minority [AFP] |

While much of the late 90s and early 2000s were relatively peaceful, an attack on apolice check post in the city of Kashgar in Xinjiang during 2008 Beijing Olympics heightened tensions in the region. The government blamed the incident on the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, which it designates a terrorist organisation. However, no independent sources were able to verify the claims made by the state.

In 2009, rioting in the capital of Urumqi led to the deaths of close to 200 people. Subsequent clashes between the police, Uighur and the Han led to large scale arrests and disappearances. Mosques run by Uighurs were forced to shut down in the aftermath of the attacks. In 2014, a knife attack killed 29 people on a train, and wounded some 140 others. The government once again alluded to Uighur separatists as the cause of the attack, clamping down on the community collectively.

Dissatisfaction runs high among the Uighurs who today face severe difficulties in finding work; most top government and private jobs are taken by Hans, adding to the frustration of the Uighur who now also have to deal with the government chipping away at their religious freedoms.

Hui Muslims

For the Hui – China’s other major Muslim group – relations with the government are far more cordial. The Hui are ethnically related to the majority Han population and share very similar cultural practices, making their integration into Chinese society far easier.

|

The Chinese government has sought to portray separatist unrest in Xinjiang as an Islamist-jihadist problem |  |

In fact, the Chinese government has in recent years attempted to be more accommodating towards Hui Muslims, a sign of its blossoming relationship with Muslim nations abroad. Last year, the Chinese government opened aDisneyesque Muslim theme park in the city of Yinchuan in the Ningxai Hui region, to promote and celebrate the history of Chinese Muslim culture, and to attract foreign Muslim tourists.

| The newly built Hui Muslim Cultural park in Yinchuan, north China’s Ningxia province. Ningxia is fast becoming the main hub for trade between China and the Arab States [Getty] |

Yinchuan is now also home to the China Arab expo, an effort by the government to push cultural and economic ties with Middle East nations.

However, no such efforts to celebrate the Chinese Muslim identity are taking place in Xinjiang. Instead, an effort to suppress Islamic cultural practices is on the rise, reflecting China’s complex behaviour and actions towards its diverse Muslim population.

Playing the Islamic extremism card

Like several of its contemporaries on the world stage such as India, Syria and Israel, the Chinese government has sought to portray separatist unrest in Xinjiang as an Islamist-jihadist problem, jumping on the 9/11 bandwagon to justify their repressive policies as a countermeasure to unsubstantiated claims of increasing “jihadism” in the region.

|

However the Uighur’s aspirations for autonomy mirror those of the Tibetans and the Taiwanese, rather than a desire to establish an Islamic emirate |  |

The Chinese government is certainly aware that this “War on Terror” rhetoric and fear-mongering holds significant cache with many western audiences, helping mask the ethnic roots of the conflict. The Communist Party Secretary General of Ningxia-Hui praised Donald Trump for his ‘Muslim’ ban justifying the move as vital to counter religious extremism.

At a political gathering in March this year, a high-ranking government official from Xinjiang warned leaders of the “international anti-terror situation” that is negatively impacting China, though no evidence that such a phenomenon exists on a wider scale has been convincingly presented.

However the Uighur’s aspirations for autonomy mirror those of the Tibetans and the Taiwanese, rather than a desire to establish an Islamic emirate. Though with some 20 million people in the region, and immense natural resources, the Chinese government is unlikely to heed any of the Uighurs demands that would curtail their access to the province.

It is, then, through the material and political dimensions that this conflict must be understood; rather than through the melodramatic, decontextualized and religious prism The Daily Mail that would otherwise suggest.

Source: alaraby.co.uk

Leave a Reply