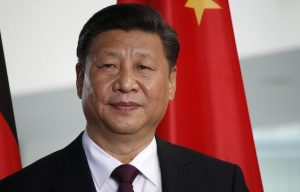

Xi Jinping is ushering in an era of Chinese illiberalism, and with it a chilling clampdown on freedoms.

This summer, a UN panel received reports of a human rights crisis unfolding in China’s far western Xinjiang province. The information showed that as many as two million people had been subjected to an intense political indoctrination and reeducation program. The backlash has largely focused on the ethno-religious nature of this crisis. Pakistan, China’s closest and most economically dependent ally, has asked China to ease restrictions on Muslims, and Uighurs (the ethnic minority group targeted) living in America are beginning to condemn China’s human rights abuses.

But over-interpreting the religious aspect of the crackdown distracts from the true nature of repression in China. The crisis in Xinjiang should be interpreted more as an assault on basic freedoms and the expansion of a totalitarian tyranny than an expression of ethnic superiority. To be sure, this is nothing less than a cultural genocide. But as far as we know, the Chinese government is not Sinicizing this group simply because they are Muslim or ethnically Turkic. It is doing so because they are a perceived threat to the power of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Intense repression has been rapidly growing throughout the country, cementing the power of the CCP in all corners of society. Indeed, the human rights abuses in Xinjiang are strikingly similar to what’s been happening elsewhere in China since Xi assumed office. Human rights reports of Xinjiang describe mass political indoctrination, the creation of a digital police state, arbitrary detention, and pervasive controls over daily life. Let’s look at each of those components individually.

Indoctrination: Mass political indoctrination is the central purpose of the reeducation camps established in Xinjiang. Elsewhere in the country, however, the Chinese government has instituted a wide variety of indoctrination programs, with the explicit goal of expanding the CCP’s control over people’s minds. This includes overhauling all of China’s major educational institutions, increasing the ideological content of all media, and controlling the spread of foreign ideas and influences within the country.

During a speech given at a Beijing kindergarten in 2015, President Xi Jinping outlined his vision of party control over education, saying, “Children should memorize the core socialist values by heart, have them melt in their hearts, and carve them into their brains.” The CCP plans to overhaul the nation’s university system to turn it into an ideological education machine. Students will undergo a hefty political indoctrination program all the way through university. Chinese professors will be forced to teach CCP propaganda. According to recent government plans, university faculty will be judged foremost by their “ideological and political performance.”

During a speech given at a Beijing kindergarten in 2015, President Xi Jinping outlined his vision of party control over education, saying, “Children should memorize the core socialist values by heart, have them melt in their hearts, and carve them into their brains.” The CCP plans to overhaul the nation’s university system to turn it into an ideological education machine. Students will undergo a hefty political indoctrination program all the way through university. Chinese professors will be forced to teach CCP propaganda. According to recent government plans, university faculty will be judged foremost by their “ideological and political performance.”

And while indoctrination and reeducation programs outside of Xinjiang do not have the same force and severity as those within the province, they are nonetheless very invasive, and are a core component of the country’s move towards totalitarianism.

Digital police state: Human rights groups have reported that there’s a digital police state at work in Xinjiang. A hyper-intelligent digital surveillance system is used to control citizens, tracking what they say, read, and do. Such a system, however, is hardly unique to Xinjiang. The government’s digital surveillance network is being implemented throughout the country. It has leveraged the ubiquitous smartphone as an ultra-powerful surveillance device, developing programs to organize phone data and providing granular, real-time intelligence on every citizen, which can be used to guide the actions of the populace and enhance the power of the state. China has also debuted a vast network of video cameras that use artificial intelligence to gather information on everyone’s actions.

Under the Chinese government, there has been a crackdown even on thought crime. Before Xi came into office, citizens had a moderate degree of freedom to have discussions privately about a variety of social and political topics, so long as they did not organize any movements or events. Those days are long gone. There are increasingly frequent reports of Chinese citizens writing seemingly innocuous messages to friends and family only to be promptly arrested.

Arbitrary detention: Reports of the Xinjiang crisis show that nearly all of China’s Uighurs are at risk of being forcibly and arbitrarily detained. Yet while more than one fifth of all arrests in China in 2017 occurred in Xinjiang (a region accounting for only 2 percent of the population), arbitrary detention is a major problem throughout China and appears to be on the rise. One of the reasons for this is the vague drafting of Chinese laws, giving authorities leeway to arrest anyone suspected of subversive behavior. Though they previously occupied a gray area where they enjoyed relative freedom, hundreds of journalists and human rights lawyers have been arrested, too.

Over the last year, there have been many accounts of arbitrary arrests for seemingly harmless behavior, raising concerns that the authorities seek to intimidate the population and encourage self-restraint. In 2017, a man referred to Xi as a coward over Wechat and was jailed for 22 months. Earlier this year, a retired professor from Shandong province was arrested while giving an interview for Voice of America.

Pervasive controls over daily life: Foreign media and Human Rights Watch allege that the Chinese government is instituting a range of controls over daily lifefor Xinjiang residents, including restrictions on religious practices. Outside of Xinjiang, a similar trend is taking place. Religion throughout the country is under assault: recently there was a crackdown on Christian churches. Christians in Henan province were reportedly forced to take down posters of Christ and replace them with portraits of Xi.

As another example, the government has increased the list of banned topics and words that can’t appear on internet content. Recently, the viewing or sharing of foreign news media was almost entirely banned. Homosexuals were once given a fair amount of room to quietly enjoy their lifestyle; now the government is becomingless tolerant in a push to reinforce “family values.” At a Dua Lipa concert in Shanghai, police dragged away audience members who held gay pride flags or even stood up to cheer.

The Chinese government’s assault on basic freedom is not a regional issue but a nationwide phenomenon. Indeed, China has lately moved closer to totalitarianism than at any time since the Mao era. The abuses in Xinjiang are a harrowing example of this pattern.

Repression in Xinjiang is more intense because the threat of regional instability is greatest there since its people have separatist sentiments, and have different ethnicities, religions, and identities. Eliminating these differences would, in their calculus, ensure greater stability. However, there is little reason to believe that if a province that was dominated by Han Chinese experienced a widespread separatist movement, it wouldn’t suffer a similar fate to Xinjiang. Sure, detainees wouldn’t be required to denounce a particular religion. But there would very likely be a system of reeducation camps set up just the same.

China, then, is not only eager to eclipse the U.S. in global influence; it is increasingly diverging from what Americans recognize as core values. America’s policymaking establishment has long assumed that, as China grows, it will become more like the West in the ways that matter most: respect for individual rights, rule of law, and, perhaps eventually, democracy. That fundamental assumption was wrong. Since 2012, China has in many ways become more like North Korea than America, creating a highly sophisticated system of neo-totalitarianism, with the crisis in Xinjiang a demonstration of that dystopia.

Congress is justified in seeking to impose sanctions on the officials responsible for the Xinjiang crisis, as it’s currently doing. However, over the long run, it needs more: it needs a strategy to counter the rapid development of Chinese illiberalism.

Source: theamericanconservative.com

Nick Taber is an analyst of Chinese public policy. He has written for The Weekly Standard, The Diplomat, and Quillette.

Leave a Reply