In China’s handling of the Xinjiang region, particularly its largely Muslim Uyghur population, scholars see echoes of North Korea and South African apartheid

he streets in China’s far western Xinjiang region are lined with surveillance cameras, even in rural villages. In some cities, police stations have been erected every 500 metres. Public buildings are surrounded with security worthy of a military outpost. Authorities use facial recognition and body scanners at highway checkstops.

Chinese authorities have treated Xinjiang as a hotbed of extremism and responded with a series of “strike hard” campaigns that have included the hiring of huge numbers of police and a visible increase in security forces.

But the effort to build social stability, particularly among the region’s largely Muslim Uyghurs, is now probing deeper into the personal affairs, thought patterns and even genetics of local residents.

What is taking place in Xinjiang has little historical precedent in the extent of authorities’ command over people’s lives, according to two scholars who recently visited the area.

“It’s a mix of the North Korean aspiration for total control of thought and action, with the racialized implementation of apartheid South Africa and Chinese AI [artificial intelligence] and surveillance technology,” said Rian Thum, a historian at Loyola University in New Orleans. “It’s a truly remarkable situation, in a global sense.”

Security in the region has risen since deadly riots in 2009 and a series of terror attacks in subsequent years. Thousands of Uyghurs have gone to Syria and joined Islamic State, and a series of stricter measures have been introduced since August, 2016, when a new leader was installed in the region.

The Globe and Mail reported on some of those changes this fall, documenting an extensive political re-education push that has sent large numbers of people into coercive study programs without charges against them.

Xinjiang has been less well-studied by foreign academics in recent years, amid government restrictions and fear of reprisal against local Uyghurs who speak with outsiders.

The entrance to the Ethnic Unity Corridor in the desert city of Turpan.

RIAN THUM

But Prof. Thum has been travelling to the region since 1999. He made his most recent trip earlier this month, and was struck by the scale of change. Among his discoveries was a kilometre-long outdoor walkway, one popular with tourists in the desert city of Turpan, that has been transformed into an extensive Ethnic Unity Corridor. It is lined with signs demonstrating Chinese government efforts at entering the lives of Uyghurs.

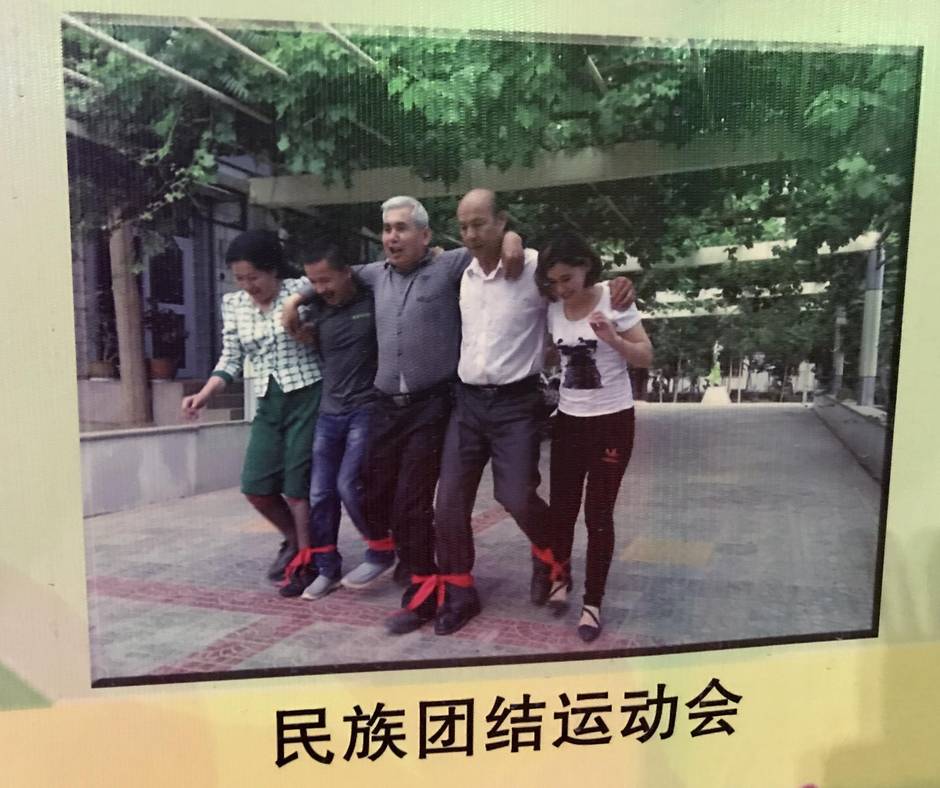

Pictures inside show Uyghurs and Chinese engaged in a three-legged race (caption: “national unity sports meeting”), classroom studies (caption: “study from each other, for the better understanding of national unity”) and a signing ceremony in which a long row of Uyghur men are writing their names on a long red banner as part of an “I am Chinese” campaign.

Earlier this month, the region required every government and Communist Party official to “eat, live and work together with local people” in a bid to “spread the spirit” of President Xi Jinping’s views on China’s future direction. Some of the official stays with Uyghurs are expected to last a week.

“I do think there might be a genuine interest in getting officials to better understand the people that they’re in charge of,” Prof. Thum said. “At the same time, there is a lot of interest in entering people’s houses and penetrating private spaces,” he said.

“All religious activities have been moved or are supposed to be moved from private and public spaces to one spot, and that is the mosque. And, of course, the mosques are heavily monitored,” Prof. Thum said.

In Xinjiang today, he said, “I guess people still have their thoughts, but speaking out loud is very dangerous.”

In June, China’s State Council Information Office released a white paper praising “great progress” in human rights in the region. It cited 129-fold gains in per-capita GDP since 1978, the waiving of litigation fees at local courts and the number of lawyers in the region.

But David Brophy, a lecturer in Chinese history at the University of Sydney, was shocked on a recent visit to see barbed-wire fortifications around public buildings and parking-lot attendants equipped with bullet-proof jackets.

“Xinjiang very much feels like a military occupation now,” he said, albeit one with an ideological objective. “Every night on TV, there was a lot of footage of oath-swearing ceremonies,” in which people pledged to root out “two-faced people,” the label given to Uyghur Communist Party members not fully devoted to Chinese policy.

“It really gave the feel of a serious purge in process,” said Dr. Brophy, who first went to Xinjiang in 2001, and at one point lived there for a year.

“The Uyghurs are basically being expected to wage war on themselves,” he added.

This April 17, 2015 photo shows a security guard in a Uyghur neighborhood in Aksu, in China’s Xinjiang region.

GREG BAKER/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Dr. Brophy was told that boarding schools are being opened in some Uyghur towns “for local children to spend their entire week in a Chinese-speaking environment, and then only going home to parents on the weekends.”

Some adult Uyghurs are also being ordered to study Chinese at night schools, a Uyghur scholar told The Globe.

Regional officials have said Mandarin-language skills are economically valuable.

The use of Xinjiang’s public institutions as tools of state control extends to the health-care system, which is being used to collect biometric data, including DNA and iris scans, from all local residents between the ages of 12 and 65, a Human Rights Watch report revealed earlier this month.

China has defended the program as useful for accurately identifying people and protecting national security, saying the collection of such data does not cause any harm.

But gathering DNA is another example of China reaching into the furthest recesses of people in Xinjiang, Human Rights Watch China director Sophie Richardson said.

“We’re seeing the state progressively infiltrate into the most private and minute aspects of people’s lives,” she said.

“It seems there’s no limit on the state’s intrusion into Uyghurs’ lives, regardless of whether they have a basis for doing it.”

Leave a Reply