Following reports of a stroke, a global guessing game has ensued, with observers uncertain as to the status of Uzbekistan’s president, Islam Karimov. While rumours of his death have been circulated by the opposition, the government has made no announcement one way or the other. Competing claims put Karimov’s time of death sometime between last Thursday and Monday. Alternatively, his daughter thanked well-wishers, stating on Wednesday that Karimov was recovering.

The uncertainty surrounding the president is par for the course for Uzbekistan, which Karimov has ruled with the aid of a personality cult since 1989. Consequently, as Uzbekistan seeks to mark 25 years of independence, the country’s celebrations are overshadowed by Karimov’s nebulous condition. The country has only known one leader, and as such his demise raises serious questions about the state’s trajectory and sustainability.

Deirdre Tynan, Central Asia project director for International Crisis Group sums up the situationin which Uzbekistan finds itself: “this is a huge test, one that has been anticipated for some time. But if Uzbekistan stumbles, if the transition turns to political chaos, the risk of violent conflict is high; and in a region as fragile as Central Asia, the risk of that spreading is also high.”

A post-Karimov Uzbekistan highlights Sino-Russian rivalry

Karimov has long been a major stabilizing force, one that has (for better or worse) kept the country together. While his ill-health is not a surprise, uncertainty does remain concerning the government’s succession plans. Rivalries and falling-outs in the ruling family have largely ruled out a direct successor. Instead, the likely candidate is Prime Minister Shavkat Mirziyoyev.

Unlike Karimov, Mirziyoyev is seen as less belligerent, and is favoured by Russia: Moscow’s diplomats never warmed to the prickly Karimov. Russia hopes that Mirziyoyev will be more pro-Russian, perhaps leading Uzbekistan to re-join the Collective Treaty Security Organization. Russia also hopes that a post-Karimov Uzbekistan would be open to joining the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). An important element for Russia is the fact that Mirziyoyev enjoys the support of ex-KGB Rustam Innoyatov – the long-serving head of the Internal Security Service. Innoyatov’s KGB credentials and Soviet-era training makes him familiar with Russia’s operating norms, thus facilitating bilateral rapport, especially with fellow ex-KGB agent, Vladimir Putin.

A power vacuum in Uzbekistan would be an opportunity for Russia to re-exert regional influence, influence that has been eroding as China pumps money into Central Asia as part of its New Silk Road initiative. Under Karimov, Uzbekistan has become closely intertwined in Chinese economic and security frameworks.Related: The Biggest Wildcard For Oil Prices Right Now

Uzbekistan joined the Chinese-led Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) in 2001, with Tashkent becoming home to the Regional Anti-Terrorism Structure (RATS), a permanent SCO organ. Created in 2002, RATS is a multilateral security agreement that creates detailed security commitments between SCO member states to combat terrorism, separatism, and extremism.

(Click to enlarge)

RATS, and the SCO in general, provides China with a framework to establish regional norms, providing uniform security protocols which in turn help protect Chinese investments in Central Asia. By hosting RATS, Uzbekistan plays a key role in the SCO. Yet, despite China’s attempt to foster regional stability, and its concerted efforts to rectify any border disputes with its Central Asian neighbours, problems remain.

Specifically, Uzbekistan continues to contest a 300 kilometer section of its 1,000 kilometer border with fellow SCO member Kyrgyzstan. On Thursday, August 25th, Uzbekistan enforced its claims, detaining four Kyrgyz men, raising tensions with Kyrgyzstan. This has led Kyrgyz president Almazbek Atambayev to order a review of the international border agreements signed by previous governments. This simmering dispute threatens to undermine SCO cohesion as well as endanger regional efforts at cross-border economic integration.

Uzbekistan’s actions, which coincide with the earliest rumoured reports of Karimov’s death, may have been an effort by Tashkent to demonstrate its strength and/or to distract from Karimov’s health.

The situation with Kyrgyzstan is further complicated as Uzbekistan is Central Asia’s most populous country, with its largest military, thus clout within the group, as witnessed by the recent head of state summit in Tashkent on June 23-24, 2016.Related: Venezuela’s Oil Output Set To Collapse As 1 Million Take To The Streets

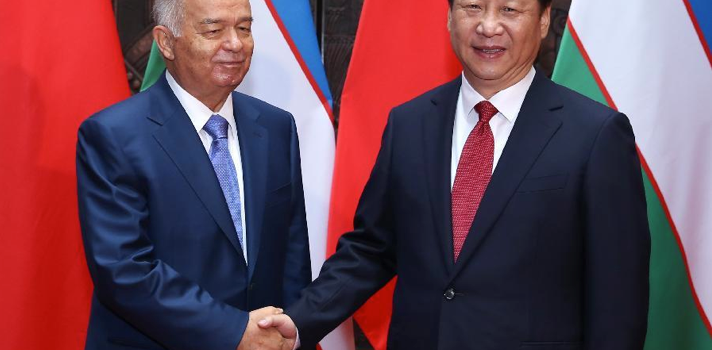

During this meeting, China vowed to upgrade its relations with Uzbekistan to that of ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’ and celebrated the inauguration of the Qamchiq Tunnel, Central Asia’s longest railway tunnel – a key Silk Road infrastructure project.

Uzbekistan is also a valuable source of raw materials for China, notably uranium, natural gas and gold (the country has the world’s fourth largest reserves). More importantly, however, is the role Uzbekistan plays in connecting China with LNG suppliers further to the west. Uzbekistan is the linchpin in the Central Asia-China Pipeline: all three lines run through Uzbek territory, as will the fourth (Line D); currently under construction.

(Click to enlarge)

The three existing lines already supply 55 billion cubic meters of natural gas a year to China. This constitutes 20 percent of China’s annual natural gas consumption. Already the largest LNG network in Central Asia, upon completion, Line D will add another 30 billion cubic meters to annual supply, further increasing China’s dependence on trans-Uzbek pipelines.

Aside from the billions China has invested in these pipelines, they are also vital to curbing China’s CO2 emissions, decreasing the reliance on coal and thus reducing pollution – a major source of civil unrest in China. These pipelines are therefore directly linked to Chinese concerns over public order and stability – Beijing’s paramount considerations.

Any instability, either due to conflict with Kyrgyzstan or due to succession chaos will have China’s full attention. A potential post-Karimov power vacuum or failed state will not only threaten Chinese economic interests, it could also offer an opportunity for non-state actors.

Uzbekistan and the threat of Islamism

Despite being a majority Muslim nation, Uzbekistan under Karimov continued the USSR’s secular policies. Karimov’s strict secular leanings, combined with his iron-grip rule led to the emergence of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU). Formed in the 1990s, the original mandate of the IMU was the overthrow of Karimov and the establishment of an Islamic state. Uzbekistan borders Afghanistan, and the IMU has long had cross-border dealings with the Taliban and Al-Qaeda; with Afghan and Uzbek fighters fighting in each other’s countries.

Karimov was long a fierce opponent of Islamic extremism, using his authoritarian rule to squash Islamist sentiment, and keep the IMU in check. With Karimov out of the picture, the IMU could use his death as a rallying call, seeking to capitalize on the uncertainty in the country. If Uzbekistan falls into a succession crisis, if its security apparatuses are weakened or distracted, the IMU could well re-establish itself as a serious threat. The porous border with Afghanistan only further facilitates the transit of weapons and fighters between the two.

To add further instability into the mix, the leadership of the IMU pledged loyalty to ISIS, with IMU emir Usman Ghasi aligning the group with Daesh in June 2015. This move caused a split in the IMU, with a splinter group retaining the IMU name, and re-affirming its allegiance to the Taliban. Going forward, this split could see pro-ISIS and pro-Taliban factions vie for influence in an unstable Uzbekistan. Since the pro-ISIS faction was defeated by the Taliban after its incursion into Afghanistan, it is likely that it will seek to re-group in Uzbekistan.

Moreover, while most Uzbek Muslims are non-denominational, 18 percent are Sunni: a potential source of support. The death of Karimov and his personality cult also presents an ideological vacuum, one that could be filled by Islamism, especially if the country’s socio-economic situation declines.

The IMU’s links to the Taliban could also see the cross-border harbouring of terrorists, creating a situation akin to that found in Pakistan’s tribal regions. The Afghan-Uzbek border could become a new lawless zone, especially given the U.S-Pakistani push in Waziristan.

IMU leader Usmon Ghazi (second left) pledges loyalty to ISIS

While this scenario would cause anyone to worry, China is especially concerned. Beijing is already paranoid about securing its western borders from insurgents, specifically militant Uighurs in Xinjiang. Indeed, one of the main reasons for the creation of the SCO was China’s effort to deny Uighur terrorists refuge in Central Asian countries. While the Uighur-Beijing conflict predates the Taliban and ISIS, radicalized Uighurs serve in both organizations.

Due to China’s experiences with Uighur terrorism, the presence of approximately 500,000 Uighurs in Central Asia, in turn makes the dominant narrative in Chinese Central Asian security relations the cutting of international links between Muslim Uighur separatists in Xinjiang and their kin across Central Asia.

Chinese fears about Islamists – Uighur or otherwise – targeting Chinese interests in Central Asia are not unfounded. Indeed, the Chinese embassy in Kyrgyzstan was bombed on Tuesday, with China identifying the perpetrator as a Uighur extremist.

If Uzbekistan falls into chaos, Islamist Uighurs working with the Taliban could benefit from a porous border and good relations with the IMU, to carry out attacks in Uzbekistan against Chinese Silk Road projects. They need not even come from Xinjiang, as Uzbekistan is home to some 55,000 Uighurs, some of whom may well sympathize with their Xinjiang kin, become radicalized, and carry out attacks against Chinese interests.

Furthermore, twenty-five percent of Uzbekistan’s 31 million citizens see themselves as enjoying close blood ties with the Uighurs. With billions in investments and 20 percent its of natural gas imports reliant on a stable Uzbekistan, China is extremely vulnerable.

Even if you take the Uighurs out of the equation, such attacks could also be carried out by other groups like the IMU. Seeking to capitalize on Uzbek instability, groups like the IMU could try to undermine the Uzbek government by hurting government pipeline revenues and undermining investor confidence.

It only takes one bomb somewhere along thousands of kilometres of a remote and isolated pipeline to cause major headaches for both Uzbekistan and China. Consequently, the death of Karimov is not merely about the demise of one man, but rather represents the potential spark for several highly dangerous scenarios.

Source: oilprice.com

Leave a Reply